|

|

|

|

|

George Washington by Charles Willson Peale,

oil on canvas, 1772

Washington—Custis—Lee Collection, Washington and

Lee University

|

This section represents the text-panel information used in the traveling exhibition.

“First in war, first in peace”

George Washington was born in Virginia in 1732, the son of a planter who died when George was eleven. Washington’s formal education ended at age sixteen, but throughout his life he surrounded himself with books.

At six feet, three inches, he was physically imposing in an age when the average male height was substantially less. A great horseman and natural athlete, he also had a fierce temper that he struggled to control. He loved the theater and had a flair for the dramatic gesture, a gift that helped him on the political stage. He was universally admired, if not always loved, for being honest and direct.

As a soldier on the Virginia frontier during the French and Indian War, Washington had his share of setbacks. But he learned from his mistakes. During the Revolution, he proved to be an astute general with a keen sense of when to attack and, just as important, when to retreat.

The figure most responsible for victory in the war for independence, he was the logical choice when Americans came to elect their first President in 1789. Once again his leadership proved crucial. Owing largely to his steady guidance, the new federal government quickly established its credibility. By the time he left office in 1797, its survival was assured.

When Washington died two years later, fellow patriot Henry Lee declared him “first in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen.” Those words are as relevant today as they were then.

|

|

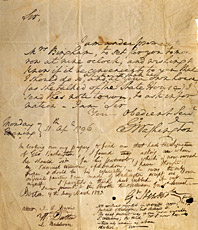

Letter from George Washington to Gilbert Stuart, April 11, 1796, about sitting for this portrait

The Earl of Rosebery

|

An American Icon

As the general who led us to victory in the American Revolution and as our first President, George Washington often had his portrait done. Everyone, it seemed, wanted a picture of the hero. But this noble Lansdowne painting best represents his importance to the new nation we were and to the great nation we have become.

We see him in the last year of his presidency, 1796. Here is a George Washington for the ages, resolute in the face of the multiple crises of our nation’s beginnings; grand in the tradition not of a king but of democracy’s representative; civilian rather than military in his authority; and above all, the embodiment of a nation both stable and free. Even the furniture around him suggests grandeur in the service of democracy: notice the oval medallion boasting the stars and stripes and draped with laurel, a symbol of victory, and design of the table leg, a symbol of united political effort. This was the man whose maturity and resolve gave us confidence in our future. The rainbow behind him breaks through a stormy sky.

Washington was lucky in his portraitist, and so are we. Gilbert Stuart had eighteen years in Europe to hone his artistry and a strong sense of Washington’s importance. Senator and Mrs. William Bingham of Pennsylvania commissioned him to provide this painting as a gift to the Marquis of Lansdowne, an English supporter of American independence. Today it provides a way to think about a time when America’s success was by no means certain, about a man whose traits of character became bound up with his nation’s fate, and about the expectation for our nation’s highest office-the presidency-at the very moment of its creation.

A Gift to the Nation from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation

The National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, is the place our country has set aside to keep generations of remarkable Americans in the company of their fellow citizens. When the Gallery first opened to the public in 1968, Gilbert Stuart’s famous Lansdowne portrait of George Washington-which was then on long—term loan-was the museum’s focal point. For more than thirty years, it symbolized the essence of the Gallery’s mission to recognize great individuals through great art.

Then, in late 2000, the British owner of the painting, who had recently inherited it, announced that it was for sale for $20 million. The staff was thrilled that it might finally be acquired, but they faced a daunting task: Who would understand the monumental importance of this icon and step forward to save it for the nation?

The appeal went out on Washington’s birthday. The next day, February 23, 2001, an article appeared in the Wall Street Journal. The following day, Director Marc Pachter appeared on the Today Show. Both alerts captured the attention of Fred W. Smith, chairman of the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, who immediately understood the patriotic significance of Stuart’s masterpiece. A few weeks later, the trustees of the foundation announced their generous $30 million gift to the Gallery, which included support for a permanent place to display the portrait and a historic national tour to bring Stuart’s Washington to the American public.

The National Portrait Gallery is grateful to the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation for saving this painting for the nation and for allowing the Smithsonian to share this treasure with present and future generations.

|

|

Apotheosis of Washington by David Edwin after Rembrandt Peale, stipple engraving, circa 1800

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

The World Without George Washington

Although he did not know it, George Washington was far from finished with his service to the country when the British surrendered to him at Yorktown on October 19, 1781. That day, a war ended and an unprecedented experiment in democracy began. Without Washington, that experiment might not have succeeded.

For all his skill as a wielder of power, Washington’s greatest asset may have been his willingness to surrender that power. After defeating the strongest army in the world, he could have used his prestige for political self—aggrandizement. Instead, he resigned as commander in chief of the Continental army and retired to his beloved Mount Vernon.

In 1787, he left retirement to preside over the Constitutional Convention, which had been called to rescue his country from political chaos. Out of that gathering came a plan of federal government that provided for a presidential office, defined with Washington in mind. As one delegate put it, the convention’s members “shaped their ideas of the Powers to be given the President, by their opinions of [Washington’s] Virtue” and the expectation that he would be the first to hold that position.

Washington ended up serving two terms as President, and he could have easily won a third. Satisfied, however, that his country’s stability no longer hinged on his leadership, he did something that few heads of state had ever done: he again surrendered his power. “It has been said,” political historian Clinton Rossiter once observed, that Washington “could have been a king but chose to be something more exalted: the first elected head of the first truly free government.”

Washington’s Life and Times

| 1732 | February 22 (February 11 Old Style): Born at Popes Creek, Virginia |

| 1749 | Appointed surveyor for Culpeper County, Virginia |

| 1751 | Contracts smallpox on a trip to the West Indies with his half—brother Lawrence; the disease leaves him scarred for life |

| 1752 | Appointed major in Virginia militia |

| 1754 | Lieutenant Colonel Washington subdues small French detachment in western Pennsylvania, an incident said to have sparked the French and Indian War |

| 1755-58 | Widely praised for his courage in the French and Indian War, especially as a commander of troops on the frontier |

| 1758 | Elected to Virginia’s colonial legislature |

| 1759 | Marries Martha Dandridge Custis, a widow with two young children |

| 1761 | Inherits 2,000—acre Mount Vernon plantation |

| 1765-66 | Parliament passes Stamp Act, imposing new taxes on American colonies. Although sympathetic to colonists’ heated objections, Washington remains uninvolved |

| 1767-69 | Becomes a leader of Virginia’s protest against Townshend duties, which were enacted on various goods shipped to the colonies |

| 1773 | Bostonians dump tea from a merchant ship overboard to protest tea tax |

| 1774 | Parliament enacts so—called Intolerable Acts against Boston

Represents Virginia in First Continental Congress, convened to protest the heavy—handedness of British rule |

| 1775-81 | Revolutionary War; Washington serves as commander in chief of Continental army throughout the war |

| 1776 | Continental Congress approves Declaration of Independence; first printed copies issued July 4

| | 1783 | Treaty of Paris, making peace between Britain and former American colonies, signed

Resigns commander in chief’s commission |

| 1787 | Serves as presiding officer of Philadelphia’s Constitutional Convention, called to consider altering Articles of Confederation, which had governed the country since 1777; his support for new Constitution becomes key factor in winning its approval from the requisite nine states |

| 1789-96 | Serves as first President of the United States after being unanimously elected by Electoral College in 1789 and 1792 |

| 1796 | Announces in Farewell Address his intention not to seek a third presidential term; warns against divisiveness of political party rivalries and hazards of permanent foreign alliances |

| 1797 | Retires to Mount Vernon

| | 1799 December 14 | Dies of a throat infection, weakened by the purging and bleeding that were common treatments for such ailments |

|